Remotely Spawning a Shell

Remotely spawning a shell

shell bind TCP

A shell-bind TCP is a computer program that implements the sockets API to listen for incoming connections and establish a communication tunnel to exchange data.

To establish a passive TCP socket with a well-known address, at least four system calls must be made (one can omit bind() to create a socket with ephemeral ports that listen on all interfaces; check INADDR_ANY).

Before Linux Kernel 4.3, socketcall() was the common kernel entry point for socket system calls. In newer versions, we can call socket’s system calls directly. So, to begin, we call socket() to prepare our socket stream.

It returns a file descriptor which is a pointer to a kernel data structure that holds the information regather the created nameless socket.

Then bind() is called to assign a local address to the nameless socket. Next, listen() prepares a queue for inbound connections, and whatever client wishes to establish a connection is placed there until SOMAXCONN is reached.

If one would prefer to spawn a shell to every client that tries to connect, a loop condition would be necessary. As I do not implement that, only the first client that connects will get a shell, and even if other clients connect they will not receive a command shell.

After reaching listen() it is noticed that the socket is ready for clients, lsof outputs show the previously created socket is willing to receive connections.

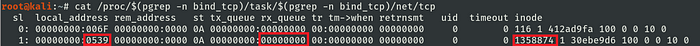

It is possible to trace attempting connections, through the kernel interface /proc/net/tcp outputs, the IP address and TCP port are disposed in hexadecimal, whenever the kernel receives an incoming connection to the bound network address and TCP port, the rx_queue is incremented by one.

no connection waiting for be accepted

no connection waiting for be accepted

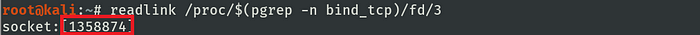

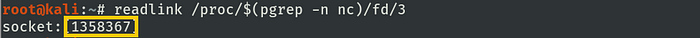

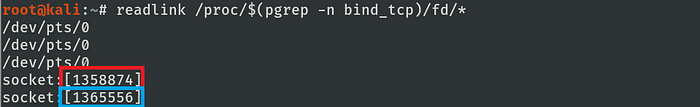

When netcat is executed (nc 127.0.0.1 1337), a new file descriptor is created by its process.

Then rx_queue of the listening TCP connection related to the server process is incremented by one, and two new entries are created related to the established TCP connection. One could notice that the server-side entry is with a NULL inode, which will change as a result of the acceptance of this client, then a new file descriptor will be generated by the kernel so it could refer to this client.

It is important to say that, if this code were prepared to receive more clients a pair of entries would be created for each new client, and whether or not it is prepared to receive more clients, the listening entry (server-side listener) will continue there.

one client wishing to establish a connection

one client wishing to establish a connection

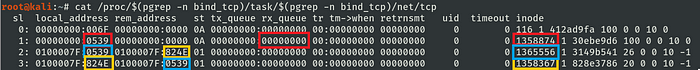

Next, accept() accepts the connection request from the first client on the wait queue, and a new file descriptor is generated referring to that socket.

Notice that, the original file descriptor is not affected by accept(). When the rx_queue reaches zero, the function blocks and waits for a client wishing to connect, but then again we have not prepared our code to accept more than one client.

new file descriptor created in bind_tcp process

new file descriptor created in bind_tcp process

The new file descriptor created is the so expected entrance that will exchange data between our application, the kernel, the network device, and our remote peer.

Then rx_queue is decremented and the two-way channel is finally established, the kernel represents the completeness of this process filling out the inode field.

connection established, original socket continues in listening state

connection established, original socket continues in listening state

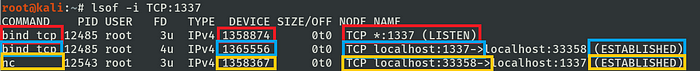

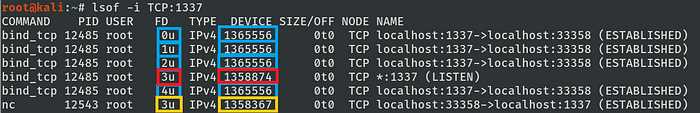

A simple lsof output shows the established two-way channel and the process command line associated with each tunnel.

Notice that, for simplicity, it shows all channels in one single host, in the real world one should find only the server or client-side from this output never both together.

The aim of a portbind TCP is to set up a listening port on a compromised host and return a command shell for the operator. To do so, after the communication channel is established it is crucial that two steps be made. First of all, redirect to the newly created socket the three standard streams which are responsible for input, output, and error. Second, spawn the command interpreter.

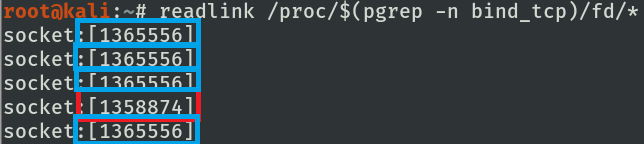

To redirect input, output, and errors, the dup2() function is used. A loop condition rewrites each standard file descriptor with the established socket fd. The concept of file descriptor can be verified in open(2).

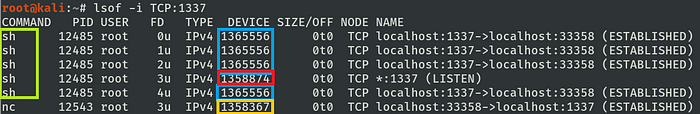

file descriptor of bind_tcp after dup2 execution

file descriptor of bind_tcp after dup2 execution

One can note that now the lsof outputs show that the standard stream regarding the server process shares the kernel resource regarding the socket that was previously established (4u).

redirection of STDIN, STDOUT, STDERR to remote host

redirection of STDIN, STDOUT, STDERR to remote host

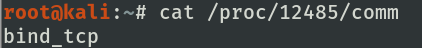

Before spawning the shell, that is, calling execve(), the /proc/PID/comm file keeps the command name associated with the shellcode process.

process command name associated before calling execve

process command name associated before calling execve

After calling execve(), the shellcode is replaced in memory by the called program, in this case, the commander, with new memory segments as stack, heap, and initialized and uninitialized data segments.

process command name after calling execve

process command name after calling execve

Then the magic happens, the commander appears in memory associated with all previous file descriptors, and now the remote operator receives a command shell through the established channel.

This is possible due to the fact that by default file descriptors remain open across an

execve().

process command name associated with command shell

process command name associated with command shell

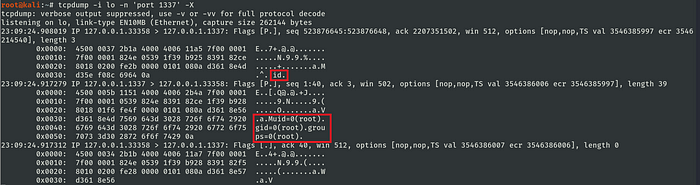

When the operator executes one command it receives the id respective to the user that executed the shellcode. It is important to say that, only a user that has the capabilities CAP_NET_ADMIN can start a listener in TCP ports from 0 to 1024.

testing returned command shell (operator’s perspective)

testing returned command shell (operator’s perspective)

Although the remote control was successfully established, the adversary must know that this channel is not secure, and one should consider establishing an SSL layer to protect their commands through the network.

As a result, it is possible to eavesdrop on the communication channel without cryptography.

code

[1] https://github.com/bugsam/code/blob/master/assembly/shell_portbind_tcp-explained.asm

references

[1] https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/master/include/uapi/linux/net.h

[2] https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/master/arch/x86/entry/syscalls/syscall_32.tbl

[3] https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/master/net/socket.c

[4] https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/master/include/uapi/linux/in.h

[5] https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/master/include/linux/net.h

[6] https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/master/include/linux/socket.h

[7] https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man2/listen.2.html

[8] https://www.kernel.org/doc/html/v5.8/networking/proc_net_tcp.html